Women in research rewarded for taking a risk

Associate Professor Uta Wille, Professor Leann Tilley, Dr Diana Stojanovski and Dr Kathryn Tiedje

By Florienne Loder

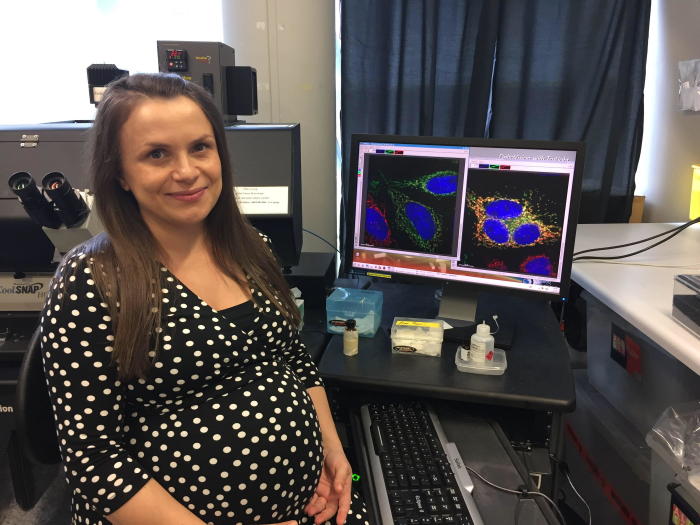

“Science is one of my great loves, it has made my life rich and taken me on many amazing adventures” says Dr Diana Stojanovski. At 36 weeks, Diana is clearly pregnant. Though a little tired, she has had a good run and still enjoys coming to work.

“It’s important for younger women to see me pregnant and working,” she says. “I have known many talented young women who opted for other careers due to the misconception that a career in science and having a family don’t mix and this is just not the case.”

Diana heads a group in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, at the Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute. Here she pursues her curiosity, delving into the inner workings of cells and studying mitochondria and its role in health and disease. Dr Stojanovski supervises two PhD students and has regular teaching commitments.

Although she wanted a family, Dr Stojanovski says she never let that influence decisions related to her career, but rather decided to just find a way to make it work. So far the strategy has fared her well and now she is expecting her second child in a few weeks’ time.

But women like Diana are departing from the Australian science sector. Just 17 percent of senior academics in Australian universities and research institutes are women. The loss of mid-career female researchers is a significant waste of expertise, talent and investment.

The Bio21 Institute boasts two female Associate Directors. But reflecting the national trend, only eight of 37 research groups in the Institute are led by women.

“It’s tough for everyone” says Associate Professor Uta Wille, from the School of Chemistry, and until recently Assistant Dean (Staff Equal Opportunity), Faculty of Science.

“The biggest worry for women is that after a career interruption they will never, ever catch up,” explains Dr Wille. “The risk is that young women become so daunted or afraid of potential challenges, that they don’t even try.”

Dr Wille began working at the newly-opened Bio21 when she returned from maternity leave in 2005.

“There is the perceived unforgiving nature of the job and the inflexibility of the hours,” she says.

“I say, you have to be realistic, but don’t give up just because it’s hard! It’s possible to make arrangements to make it work. Academia is actually more flexible than you think and it’s ‘ok’ to have a normal working life and family life.”

As a PhD student, Dr Wille was the only female in a large group of twenty students. “I really wanted to work in atmospheric chemistry and I was glad to be part of the group” she says. At the time she confronted her supervisor about his behaviour towards her, which was undermining her confidence. “All of a sudden I had his respect.”

“Communication has often solved the problem,” says Uta. “Confronting workplace issues means being prepared to have some difficult conversations. Don’t lose your integrity and don’t be afraid to stand up for yourself.”

Rather than one patient at a time, malaria researcher Dr Kathryn Tiedje wanted to help an entire community or country.

So after her PhD, Kathryn enrolled in a Masters of Global Public Health at New York University.

Here she met Professor Karen Day, who at that time headed the MPH Epidemiology stream and had established the Masters of Global Public Health Program at NYU. “Karen was also a scientist and we connected – she ‘got’ me,” says Dr Tiedje.

This serendipitous meeting would change the course of Dr Tiedje’s career, leading her to join Professor Day’s group, which moved to the Bio21 Institute/School of BioSciences when Professor Day was appointed Dean of Science, University of Melbourne in 2014.

“Science is tough. Karen saw the potential in me and was willing to take a risk. Having this confidence and support at the right time gave me the courage to change direction in my career, to move to Australia and to continue to pursue science with a focus on global health,” says Kathryn.

Only a floor away, another malaria researcher supports mid-career women to stay in science.

In 2015 Professor Leann Tilley received the Australian Research Council’s Georgina Sweet Australian Laureate Fellowship. She is developing a scheme to fund two $25,000 awards annually for women in the quantitative biomedical sciences. Nominally used to pay for research assistance, childcare, or to attend international conferences, Professor Tilley says the awards will ultimately help mid-career women scientists create a compelling research vision, to build up their track records, and to increase their confidence.

Professor Tilley names the Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences mentorship program, which attracts many mid-career women, as an invaluable way for women to gain support.

“Having mentors who encourage young researchers to be competitive and apply for awards and grants is an invaluable step in the research career journey,” she says.

“A bit of healthy competition can motivate you in your career,” Professor Tilley adds. In her own career journey, she recalls that it was seeing her peers progress through the ranks that encouraged her to go for a promotion and to work harder to get it.

----

As Diana Stojanovski commences her maternity leave she wishes to send a positive, but realistic message to young women: ”Having a family and working in science is extremely challenging, but working makes me a better mum and becoming a mum has made me a more efficient (and happier) scientist.”

Banner image: On 8 December 2015, the night of the Bio21 Ten Year Anniversary Dinner, the women of Bio21, a formidable line-up of successful and talented female scientists, spontaneously organised themselves for a photograph at the front of the stage.

This article was first published on Pursuit. Read the original article.