Media Release: Toxoplasma parasite’s greedy appetite might be its downfall

13 August 2015

Researchers are a step closer to developing drug targets for Toxoplasmosis, after gaining insight into its unique feeding behaviour.

Toxoplasma gondii is estimated to chronically infect nearly one-third of the world's population, causing the condition Toxoplasmosis. It is most commonly associated with handling cat feaces and is a particular threat to pregnant women and immune-compromised individuals, such as HIV/AIDS patients

It may even be implicated in mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and depression.

Toxoplasma has an unusual ability infect any warm-blooded animal cell, from immune cells to brain and muscle cells.

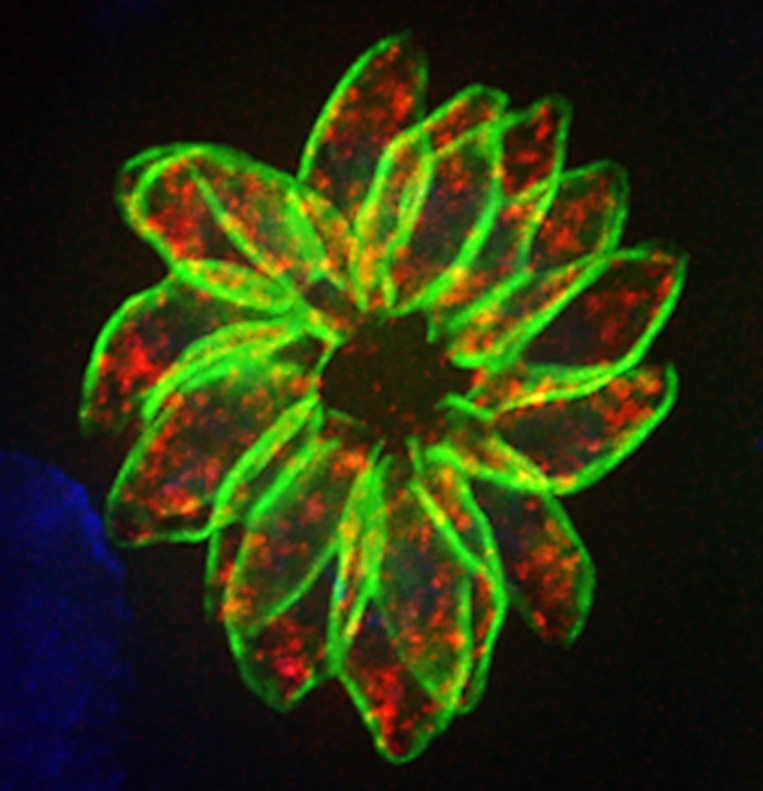

A study led by researchers at the University of Melbourne’s Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute has shown, for the first time, the extraordinary capacity of Toxoplasma to infect and grow within these cells, is due to its very broad culinary tastes. The research was published today in the journal Cell Host and Microbe.

Scavenging nutrients, such as glucose, from the host cell is one of the biggest challenges that microbial pathogens face.

Lead author Martin Blume and colleagues demonstrated that Toxoplasma is able to steal and utilize a range of energy-rich nutrients from the host cell, allowing it to adapt to different host cell niches.

“Unlike other pathogens that tend to only use one nutrient at a time, Toxoplasma gondii, can use multiple nutrients at the same time. This may give these parasites enormous flexibility as well as the ability to grow in a range of different host cell types,” explains Professor Malcolm McConville, senior author and Director, Bio21 Institute, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

While being adaptable is good, it comes at the cost of having to make all of the enzymes need to metabolise these nutrients all of the time, an apparently wasteful exercise. However, the researchers have shown that Toxoplasma has repurposed some of these enzymes so that they improve nutrient catabolism regardless of the nutrient being used.

Toxoplasma has managed to tweak its metabolism in a way that allows it to be both more adaptable and more efficient, allowing it to colonize a new animal or human host and grow very rapidly.

This survival advantage may also turn out to be its Achilles’ Heel. The researchers show that at least one of the enzymes that is switched on all of the time, TgFBP2, is also needed all of the time even when parasites are using nutrients that are not normally catabolized by the enzyme. When the function of TgFBP2 is blocked, Toxoplasma is no longer infective.

This new insight makes it possible to develop drugs that specifically target and block TgFBP2 and prevent acute Toxoplasma infection.

For interviews, contact Professor Malcolm McConville, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Melbourne on 0478 408 681.

Alternatively contact Jane Gardner, External Relations, University Services: 8344 0181/ 0411 758 984