Director's Message - A protein, a project and a new department - 21 October 2020

The news cycle is short, but science stories of discovery are long, sometimes spanning decades. I’d like to share a tale of a science story that has been keeping me busy for over a decade. Although we celebrated a milestone a few weeks ago, it didn’t make any headlines and was drowned out by more urgent news of the day. I’d like to share it here.

The news cycle is short, but science stories of discovery are long, sometimes spanning decades. I’d like to share a tale of a science story that has been keeping me busy for over a decade. Although we celebrated a milestone a few weeks ago, it didn’t make any headlines and was drowned out by more urgent news of the day. I’d like to share it here.

Professor Karlheinz Peter of the Baker Institute contacted me in 2008 after reading a media release about my work. He was interested in my expertise as a structural biologist and as we got to know each other we soon realised that we shared a common interest: we were both fascinated by the protein ‘C-Reactive Protein’ or CRP.

Karlheinz, a cardiologist, used CRP as a diagnostic marker for inflammation, but as a researcher he wanted to know more about this protein. What role did it play in inflammation? Was it just a marker, or did it cause or exacerbate inflammation? And what would happen if you could block its function?

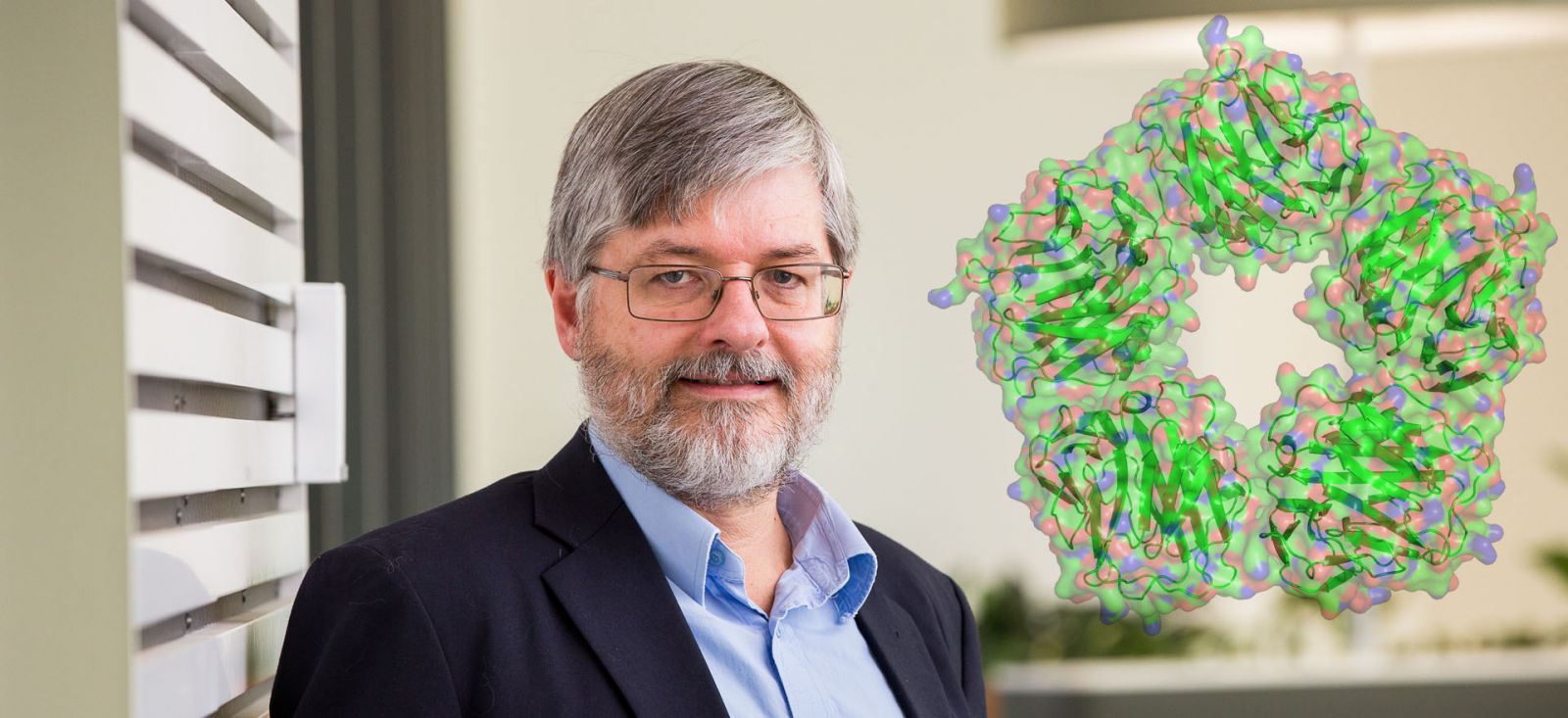

I too was interested in this protein. Its 3D atomic structure had been determined in 1999 revealing a remarkable donut-shaped pentamer but little more was known about its function. What did it bind to, where and how? What effect did binding have on the behaviour of this protein and the immune response?

Combining biological in vivo tests and computational biology studies from the two teams, we revealed a new species of CRP, called pCRP*, that we published in Nature Communications. pCRP* was found to be the major CRP species in inflamed tissue and was shown to be responsible for activation of an immune response via the complement pathway. We also had a proof of concept that when membrane binding of CRP was blocked by the small molecule inhibitor, 1,6-bis(phosphocholine)-hexane, inflammation was abrogated.

We’d proved that blocking CRP stopped inflammation, but the small molecule we’d used was not suitable as a drug. Since then we’ve been scouring libraries of molecules for suitable candidates, modifying and testing them. This is an ongoing process, bringing together complimentary approaches, carried out by members of our respective teams.

Tracy Nero, Craig Morton and Steffi Cheung have been handling the computational modelling and drug discovery, drug binding assays and structural biology.

Karlheinz Peter’s team includes medicinal chemists, Guy Krippner and Geoff Pietersz, haematologist James McFadyen and a collaborator at the University of Freiburg, microsurgeon Steffen Eisenhardt. It became evident that bringing our complementary knowledge to cardiovascular problems was an incredibly effective way to drive this research.

As Karlheinz observed: “When you look at cardiovascular research in Melbourne, there are many excellent scientists across the city. If you manage to combine this unique skill set, especially across disciplines, then you have an enormous potential for collaborative research addressing cardiovascular health problems.”

And so this year a new Baker Department of Cardiometabolic Health in the Melbourne Medical School at the University of Melbourne was formed. It brings together research groups from the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute and the University of Melbourne. The new department is focusing on research and innovation to improve the lives of people with, or at risk of, cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes. Its work will include developing novel targets and therapeutics, using big data and new technologies, such as genomics, to transform prevention, diagnosis and disease management, a focus on clinical translation and contributing to clinical service delivery and prevention.

At Bio21, the Ascher, Donnelly and Parker groups are members of the new department. Among others, our ‘CRP’ project was selected for $200,000 seed funding from the new Department to progress our drug discovery work.

“Combining the expertise at the Baker Institute and the University of Melbourne through the new Baker Department of Cardiometabolic Health, allows us to harness all the unique talent and expertise available at both institutions. It works when the human ‘chemistry’ is right, but it also provides the environment to foster interdisciplinary collaborations, which often deliver the most disruptive scientific advances,” says Prof Karlheinz Peter.

The ‘CRP’-collaboration story started with a media release and a meeting more than 10 years ago. The conversation sowed the seeds of an idea for a collaboration. It has developed into a promising drug development project which is now being progressed under the auspices of the new Baker Department of Cardiometabolic Health, created in a partnership between the Baker Institute and the University of Melbourne.

But this is not the end of the story; it’s possibly just the beginning of the second chapter. Inflammation is increasingly being implicated in a range of conditions from heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, autoimmune diseases and even Covid-19. With the seed funding and the new Department and resources of Bio21, we are in a great position to take the next steps.